What is Collaboration?¶

While the word is well-defined — modes and types of collaboration vary, especially in science where the concept of collaboration stretches from reviewing someone’s paper through to relationships around research that involve groups of people spanning years or decades.

When we think of collaboration at Curvenote, we are specifically thinking about how people collaborate around distinct pieces of scientific work.

Of course, this includes co-authoring researcher publications which may occur within a series of months or years, but it means looking at how people collaborate day-to-day and week-to-week through writing, documents, data, and computational artifacts just as Jupyter Notebooks.

The majority of collaboration within closer peer groups happens through frequent communication; seminar papers & discussion documents, presentations, technical reports, research meeting notes, research plans — all of which build a body of information and threads of learning, analysis, and discussion, which often culminates in a journal paper or thesis. But it’s the whole body of work and related artifacts that fully represent the research and process that was undertaken to reach the results.

In moving towards open science, researchers are striving to make more of this body of work openly available, their datasets, working documents, code, and preprints in addition to the final open-access publication — creating a package of work that can be more readily built upon and reused.

At Curvenote we are interested in creating technology and collaborating on infrastructure to support the entire process. We think about how to lower the barrier for more scientists to be able to work in this way while maintaining first-class support for open-source technologies and protocols that underpin modern science. This can spawn new relationships, connections, and collaborations and bring together people who would not have otherwise collaborated or contributed to a piece of work.

Some collaboration scenarios like close real-time collaboration, demand significant technology features, while in other scenarios, a single simple feature can significantly improve the collaboration experience in a number of ways, making it much more effective.

In this post, we talk about some distinct modes of collaboration and the technology and software features that support/enable them. We’ll focus on three modes:

- Gathering feedback - asynchronous, broad & external collaboration

- Asynchronous co-authoring and review

- Real-time pairing / simultaneous editing

Gathering feedback¶

This is likely one of the loosest forms of collaboration, typically asynchronous with a long cycle times — gathering feedback from a diverse group can be a significant amount of work. Not just in engaging or preparing the material, but in collecting and processing the feedback itself, which can sometimes come in various forms.

We’ve heard experiences of very difficult feedback cycles; a researcher emailing a draft document out to collaborators, to receive a variety of responses. Sometimes edited documents with comments interjected in the flow, responses in an email separate from the draft, PDF scans of printed copies with handwritten margin notes, multiple copies of the Word document sent back by email, Dropbox, or Google Drive.

Processing that feedback and incorporating it into the next draft can often require just as much work as the original study itself. The feedback process should be and can be much easier.

Sharing & Commenting¶

Two simple features that are taken for granted in so many apps we use today (just think about how social media works) can completely change this workflow.

Create drafts in a shared environment - Google Docs is a go-to workaround for many people as collaboration is good, but it lacks support for scientific writing, which is where Curvenote excels.

Share your supporting information - To get useful and constructive feedback you need to formulate your “Ask” and provide those notes along with your manuscript. Curvenote projects let you give your collaborators access to multiple documents, such as guidance notes, manuscripts, and supporting materials (e.g., Jupyter notebooks), so everyone is working on the same page, in the same place.

In-place commenting - Threaded commenting in a manuscript allows feedback to be provided and conversations to happen in-place and right beside the content it refers to. This is the ideal context for feedback; it encourages discussions over duplication and collaborators also get the chance to interact. A solid real-time commenting system with threads, notifications, and resolutions is of real benefit and makes it much easier for the author to gather and incorporate feedback. Everything in one place, everything in context.

Asynchronous Coauthoring¶

We aren’t always sitting right beside our co-authors and even when we are it doesn't always mean that we write together. Often we’ll plan our manuscript, divide labor and draft our different sections to later cross review, revise and contribute to each other’s pieces to author the whole document.

Most of this authoring is going to happen asynchronously, but we want it to happen in the same place, without having to merge documents or get tied up emailing or spreading updated copies around via Dropbox. For this to work you need a solid authoring environment and Google Docs has been an attractive go-to for many people.

While Google Docs is a great tool for content co-authoring, the big drawback for us scientists is that Google Docs isn’t a scientific writing environment. It doesn't nicely support many of the features we need; equations, cross-referencing, citations, footnotes, figures, and tables with numbering and captions — not to mention integrated datasets or computation for interactive figures. Thus, if used for raw text, it will inevitably have to be copied out and integrated into an environment where a manuscript can be constructed.

Version Control for Writing¶

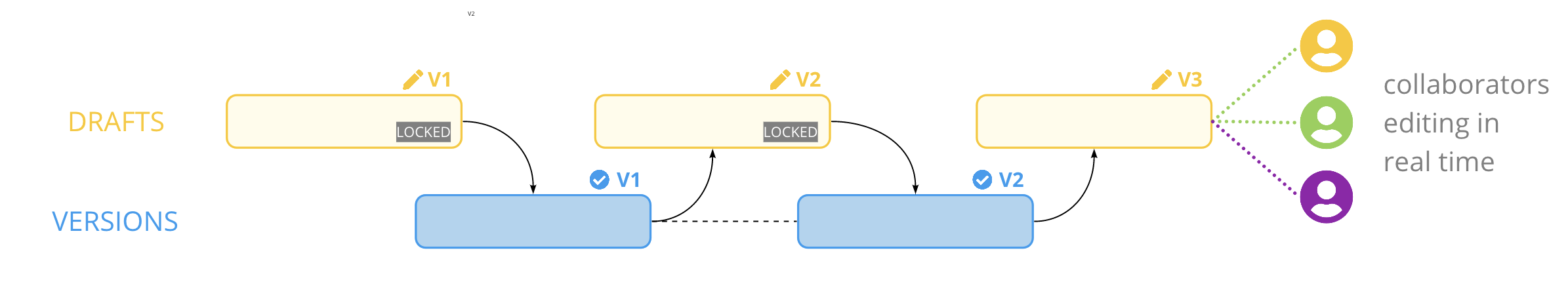

A scientific editing environment with clear integrated version control can really help here.

A manuscript is started in a shared environment (in Curvenote we call these projects) and authors can collaborate independently: adding blocks of content to the draft. Authors save their blocks as they progress and built-in version control makes it easy to see the progression and changes that people make.

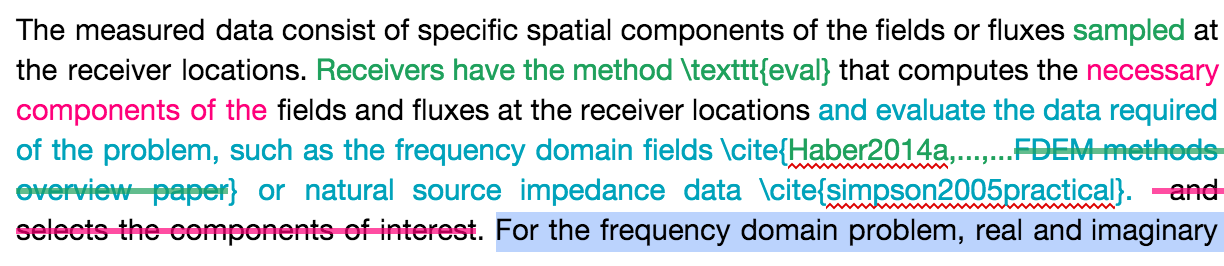

In the early stages of the draft this co-editing works smoothly but as the work progresses, and authors begin modifying the shared content and refining sections originally written by the others, and the editing process becomes more tentative. Built-in version control means it’s easy to look back before edits were made and identify changes through “diffs” — the difference before and after a change.

In the later stages, edits are made more sparingly and conversations begin to appear in comments to discuss potential modifications. This is when “suggest changes” features come into their own.

Suggest Changes¶

While leaving comments in the draft as co-authors work will always happen, they are often not the best place for suggesting new text changes.

A solid suggest mode feature can speed up integrating contributions and gives co-authors the confidence to change the text in the first place. As all changes are in place you can view the content close to its edited form but also see easily what has been removed from the text, and how the flow of the prose is affected. Different software tools have experimented with the format of suggesting changes over time, from inline markup to balloons.

We prefer the inline style of Google Docs because it is relatively clear to read and each change is accompanied by a floating control in the margin, making it easy to isolate and accept to reject the change.

We don’t yet have a “suggest changes” feature available in Curvenote, but it’s firmly on our roadmap so watch this space.

Pair Authoring¶

We’ve adapted a phrase here from the software development world where pair programming is the practice of multiple programmers working simultaneously on a single change or task.

While this may seem less productive, pairing improves quality, reduces defects, and improves team communication. Multiple sets of eyes and an active conversation around the changes being made lead to a better implementation and the additional time spent is recovered through better designs with fewer defects Cockburn & Williams, 2000.

Of course, mileage varies depending on how well the process is supported, and the task at hand but what was previously something that was only possible for developers in the same room, is now both possible and actually more effective when developers are working from their own machines. This is because of the availability of real-time collaboration sessions supported directly by a developer’s coding environment.

Real-time collaboration¶

Real-time collaboration is a feature that allows multiple users of a software tool to edit a document simultaneously. This allows people to see others’ changes in real-time and incorporate their changes into the flow as the content updates. Naturally, this means that people can work on a single draft of a manuscript and immediately cut out working in different versions or creating subdocuments to work in on their own, only to later re-incorporate them.

Real-time interaction like this also promotes new behaviors. Authors can watch others type and join them in the writing flow, whether that’s mopping up typos, filling in references, or continuing the thread after one writer pauses. It is impressive to watch how a good collaborative writing environment can pull together a set of authors to produce a consistent piece of writing.

Like in software development, this type of activity is synchronous and requires some scheduling if not planning. Curvenote’s editor fully supports real-time collaboration allowing you to work like this right now and have a pair authoring session on your paper.

Often you can also benefit from being on a voice or video call at the same time, and here at Curvenote HQ, we’re often on Google Meet or Zoom so we can confer while working on a document.

Figure 4:Image by Marvin Mayer - https://

We have two important features at the top of our roadmap - presence and interactive cursors. If you’ve used Google Docs or other online collaborative editors, you’ll recognize these features. We’re expecting these will improve our real-time collaboration experience - and we’ll incorporate our own flavor of this UX pattern, meaning you’ll see who is actively watching and editing a block as well as seeing their cursor when they have a block in focus, are typing or have made a selection.

Collaboration doesn’t stop there¶

Of course, collaboration doesn't stop there, there are more collaborative models with their own nuances, needs, and ways they can benefit from certain technology features.

Activities like open community authoring or open community reviews are interesting models. While Wikipedia springs to mind as a massive community-driven authoring project supported by a specific technology “The Wiki”. Another interesting example is GitHub and the increasing use of GitHub as a repository for scientific work in various forms: Markdown documents, posters and papers in pdf form, data, code, Jupyter notebooks, interactive HTML documents, and books.

We are seeing researchers leverage existing technology from software development for version control, archiving, and software documentation tools to produce repositories for work that are open, and can be accessed to reproduce and re-use or build on the work. The community features around these tools enable discussion and contributions from multiple actors, encouraging connections and collaboration between a wider group of researchers who perhaps wouldn't have otherwise come together.

This is a powerful example of how supporting technology can place a transformative role in collaboration and interaction and is something to support as we move towards open science.

At Curvenote we are creating technology to support these new ways of collaboration that are tailored towards technical writing and communication. We believe that these can help change how we interact with and progress scientific work.

Curvenote is a writing platform with first-class support for scientific and technical writing, real-time collaboration, and integrations to the Jupyter ecosystem. Try it out for your ongoing research, thesis, next paper, or project.

- Cockburn, A., & Williams, L. (2000). The costs and benefits of pair programming. Extreme Programming Examined, 8, 223–247.